A Place for Everything

In a world that worships death cleaning and minimalism, guest author Karen Kemp makes the case for mess - and for the unexpected intimacy it brings with those who came before.

My mother was the most well-churched person in my life, yet the Rev. John Wesley’s maxim — “Cleanliness is next to Godliness” — clearly had no influence on her. Her home craved a purge and a scrub. Stacks of magazines and newsletters teetered on the coffee table leaving barely a square inch of table visible. Like Zorro, I boldly scrawled my name in the bookshelf’s dust. Dirt tracked in on boots migrated to the kitchen’s edges and devolved into grime, topped like a layer cake with white cat-hair frosting. One cabinet was jammed full of pancake mix, Hamburger Helper, and pasta salad kits — a comprehensive inventory of American quick-fix processed foods, many with near-historic expiration dates.

Wesley was talking about spiritual purity, not tidiness. But by the time his message reached me, its meaning had morphed. It meant a tidy home was good and living with grime and clutter was … evil? Well, definitely not good.

Now in the downsizing phase of life, I’m reflecting on cleanliness and simplicity. How an uncluttered space can have a calming effect. The way possessions can be utilitarian, inspiring, talismanic, artistic expression, aide-mémoires, or burdens. How excessive organization and uniformity can stifle creativity. The spiritual and ethical dimensions of simpler living. And, the way a loved one’s belongings can reveal stories that were hidden.

Good, Not Tidy

I began visiting Mom for the summer in my teens, after my parents divorced. I arrived with fresh eyes. The clutter in her disordered place was a challenge I felt sure I could conquer. “Mom, do you truly think you will ever read that magazine? Let’s ditch the outdated canned goods, OK?” My mom would offer a weak protest, vexed by the sin of waste. But she was a “go along to get along” sort of person. She agreed to discard things, thanked me for lifting teeming knickknacks to dust the windowsills, expressed gratitude for my help. I admit, I felt slightly superior. What was so hard about this?

Since my smug, judgmental phase, I got married and had children. Like my mom, I worked full-time and didn’t hire anyone to help at home. Result: Dog hair on the furniture and dust tumbleweeds under the beds. Instead of cabinets overstuffed with cake mixes, I collected books and artsy animal figures. I saved my children’s art projects.

In no time at all, it became clear what was so hard about this. Eventually I accepted that even though I wanted a tidy home, making it happen would never rank very high on my priority list.

Actually, I tried to accept it.

In truth, the association between “tidy” and “good” was embedded in me like a thorn. Concerned about what visitors would think, I flash-cleaned in advance. Friends’ orderly homes stirred envy. Living with stacks of books I hoped someday to read and dried dog drool on the kitchen floor left me feeling an undercurrent of less than. Looking back, I think tidying my mom’s house was an attempt to give myself a status makeover.

‘Imagine Your Ideal Lifestyle’

Managing our stuff is a chore, no matter what our financial status. It’s such a first-world challenge that a whole industry exists to help us. The KonMari Method advises to first “imagine your ideal lifestyle.” Then ask yourself if an object “sparks joy.” If it doesn’t, bye-bye birdy figurine. Next, choose a place in the home for each item you’ve kept. Even getting started with this method is hard for the mercurial among us, whose joy might be sparked one day and not the next. For parents, there’s an added challenge – will my child miss this memento?

A successful novelist described shedding a lifetime of accumulated belongings with the popular “three piles” approach: Things to trash, things to give away, things to keep (the smallest pile). In her kitchen, she found seven sieves. She uncovered similar excess in every cupboard and closet. She gave a set of silver to a young friend soon to be married. Caving in to nostalgia, she kept the mothballed vintage typewriter where she tapped out her first book. By sorting, deciding, and donating she prepared for her date with Death.

I envy her. All those decisions are behind her. For me, they loom ahead. I have overstuffed kitchen cabinets and closetsful of unworn clothes and once-beloved toys of my adult children. Hundreds of books. When my father died, I acquired his Camry, a mahogany bedroom set, socket wrenches, two or three photo albums, and his books. I thought reading his books might help me better understand this complex, confounding person. (This is still on my to-do list).

More recently, my mother died, too. She had moved and downsized twice, thank goodness. Even so, more souvenirs came my way. Dozens of photo albums, maps with yellow-highlighted trip routes, Playbills, Christmas and birthday cards, the secretary desk where she sat to write letters — and she wrote many letters. Plus, more books.

Now, I must wrestle with dad’s and mom’s things as well as my own.

A Secret Door

The decluttering novelist believes it’s unfair to make others redistribute her stuff. No question, it is a job. It can be a gift, too. It can help us more deeply know lost loved ones. As a teen in my childhood home, I stumbled upon a poem my father had written as a young man. It was a powerful metaphor for how passion can destroy you. After he died the poem was nowhere to be found. Someone had assiduously purged his files of telling details, maybe my father himself.

My mother, on the other hand, left a paper trail. A massive one. By following it, I learned she was an excellent science student. I read her middle school report on the work responsibilities of an executive secretary. In her youth, girls could look forward to being a secretary, a schoolteacher, or a nurse (the path my mom chose). Reading this list of choices in her own handwriting opened a secret door. I walked into her childhood bedroom and looked over her shoulder as she sat at her desk writing the report, imagining her future.

My mom kept meticulous financial records, just as her mother had. This skill helped her extract the correct short-term disability payment from an insurance company after she cut her finger slicing peppers. Reading through relics of her past, it struck me like a cartoon anvil falling from the sky that, while I am a word person, she loved numbers. How had I missed this?

With grief as my quiet companion, I keep winnowing her stuff. It’s work, but it’s also a journey of discovery. What we save reflects our values and our striving.

In my mother’s labeled photos I see the smiling faces of her friends. I see the travel adventures she enjoyed with her third husband, long after she fled the prison of marriage with my father.

I see things I was too busy to see when I was raising my children. Now I appreciate why my mother’s house was no showplace. She was busy writing letters to friends, planning trips, volunteering at her church rummage sale, and ushering at the local summer opera house. She loved people, and they loved her.

Messy Life

Buddhism teaches us to reflect on impermanence. All our acquiring and aspiring must end in letting go. Shedding earthly belongings can help us prepare, corporeally and spiritually, for the mystery that awaits. By righting our wrongs and getting our paperwork in order, we strive to control the uncontrollable.

Discarding things is easier for me now; I’m aging. Even so, like my mom, death cleaning will never be a priority. Most ways to “spark joy” don’t revolve around keeping an organized home. Many life experiences await, and finally I have time for them. Sure, I’ll keep downsizing. But my kids should be ready for a bit of a mess.

Karen Kemp is a writer, editor, mother, and grandmother who lives between the mountains and the sea in North Carolina. She loves wild places, animals, learning, art, and hiking up steep hills to enjoy the view. Her previous piece in Certain Age, “Dispatch from the Edge of Hope,” details her journey by canoe in the DR Congo to see bonobos in the wild.

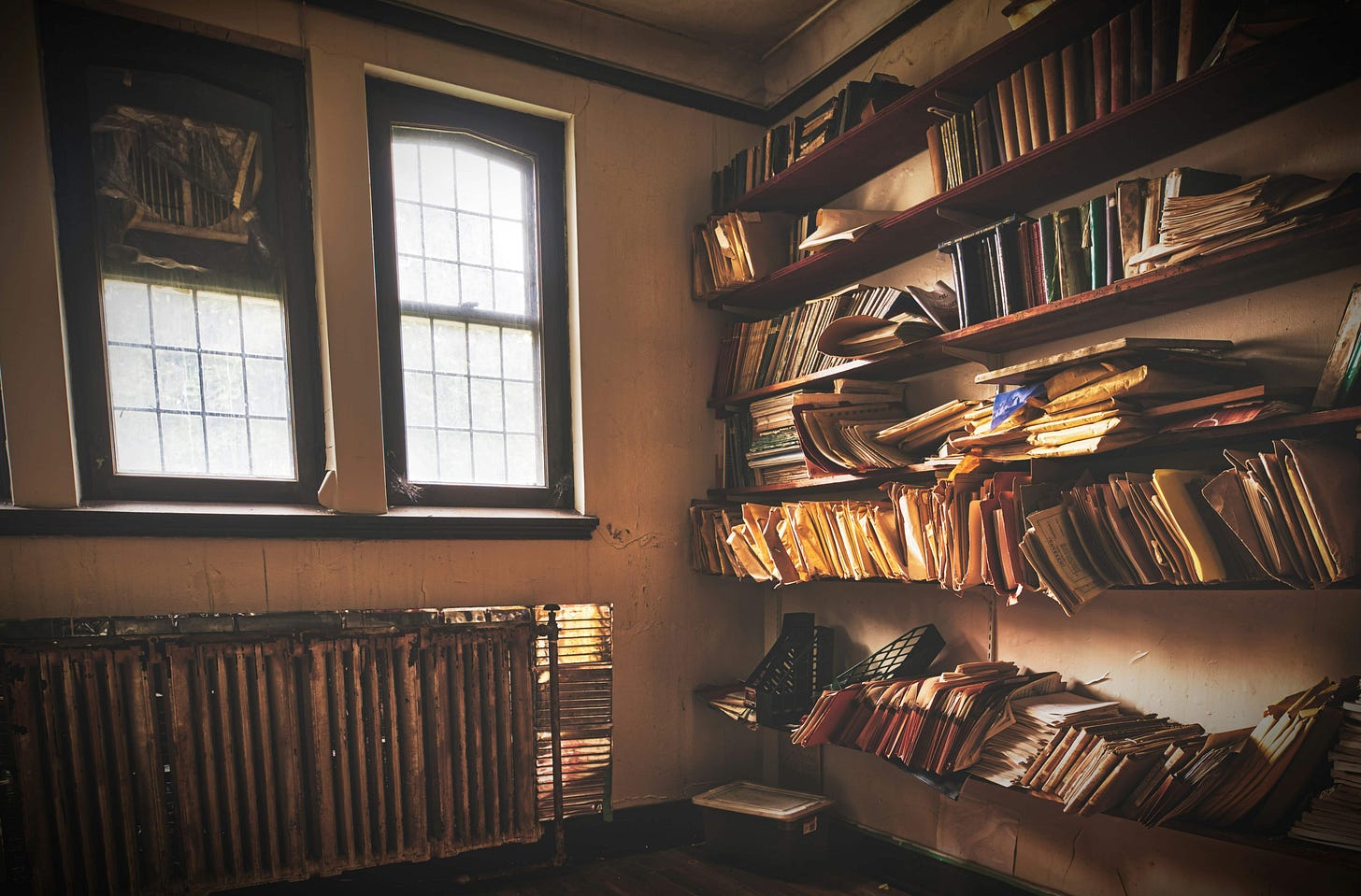

Image: Bookshelves by JF Martin

If you enjoyed this post, give it a like ❤️, restack it, or comment. That tells the algorithmic deities to share it. Thank you!

A friend once told me...

"Entertain in the evening, and then you only have to dust under the lamps."

Certainly works for me.

Loved this piece; my very patient daughter is currently play your role.

Quite delightful and humorous as well. I had images of my own dear mother who cared nothing at all for tidy areas. Reading books topped her list of what to do when she wasn’t running a nursery business.