The Paris Apartment

In this ghost story with a disco beat, Andrea comes to Paris, armed with a fellowship. But an unexpected – and otherworldly - roommate shows her that the city has bigger plans for her.

It is September when you arrive. The wind carries cold on its breath, a warning that winter will strike before long. But this is Paris. You have always wanted to live here. What is it about this city? You climb the steps out of the metro at the Anvers stop. You’ve just arrived after flying overnight and between the jetlag and lugging your suitcase on the metro, the sunlight caressing the limestone buildings and smell of dying leaves hits you right in the heart.

Finally, you think. I’m here.

You’ve been to Paris before, as a child with your parents, after college with your girlfriends, then once, later, with a lover. You’ve studied its history. Named Lutetia by the Romans and sacked by marauding Vikings — a chain across the river designed to thwart the approach of their long boats, but it didn’t. The early city nestled onto an island in the Seine, the Ile de la Cite. It houses the famous cathedral, which, in the long tradition of cathedrals, is closed after fire nearly brought it to the ground. Round and round the history winds, mirroring the city’s concentric plan — like a moon shell, coiled and chambered, each era and arrondissement yielding unexpected treasures, fresh insights. Paris, like the self, spirals, assimilating waves of conquerors, emigres, artists and bureaucrats, hopeful or world weary, seducing them in its blue haze, then showing them — and you, maybe? — new facets as time moves them in its gyre.

You have come on a Fulbright, armed with your newly minted Ph.D. in historical textiles. Your project is to map the cartoons — tapestry templates, not comics — in the Gobelins Manufactory. An art history genome, you called it in your proposal, and you bring a geneticist’s rigor to the work, cataloging, classifying, clarifying the history and material innovation that led to the vast woven works of art, that sadly look like tatty curtains in so many renderings. Literal backdrops. You will reveal their glory, the intricacy of their making, the vast exchange of money it took to create them. Every aspect of them fascinates you. This city, this project — and money enough to dig deep for two years. It is your dream come true.

Of course, Paris is a container for many kinds of dreams, not all of them scholastic.

Online, back in Connecticut, you found an apartment on the Butte Montmartre — the hill of martyrs. It is not necessarily the neighborhood you envisioned in your dreamtime rendering of this life. That of course was the 6th, Saint Germain des Pres, storied haunt of radicals and writers, and now impossibly beyond your means. Or maybe the 10th, with its canal and edgier chic. Montmartre, the city’s one hill, is the home of the ersatz Paris you disdain. Your parents brought you there out of an invisible duty to “see the sights,” a Puritan form of travel in which duty substituted for fun. You walked through the Sacre Coeur, impressive when you were younger, but now you know better. Not on a par with Notre Dame, though few things are. With your girlfriends after college, you walked up the hill at sunset and eyed the women with their lovers, wondering, what would that be like? It was hard to imagine any of the boys you knew in college caressing the back of your neck so deftly, knowing how to find that spot that unleashes tingles, as these men seemed to do. No, you had ruled out this area as not interesting, not au courant, not for you. Montmartre has no place whatsoever in your dream.

But there it was, the perfect apartment. Small of course, but on a top floor with a pair of large windows. One looks out over a leafy street, the other takes advantage of the hilltop location and gazes out to the city. At least, that’s how it appeared online. Soon you’ll know. And it is within your means, thanks to some negotiating with the landlady, who, it turns out, has a soft touch for art history. You promised to take her into the archives at the Gobelins, and here you are, rolling your suitcase up and around the hill, another spiral. Halfway, there’s a merry-go-round. How the French love a carousel. You pause here, watching a little girl in a blue dress and red shoes, riding a unicorn — she’s reaching for its horn, then waving to her mother standing nearby with a woven bag of groceries and a younger brother looking up, rapt. The girl’s cheeks bloom with excitement as if she’d been painted with a pink rose. Straight out of Renoir. Leave it to the French to perfect childhood.

You reach the square at the top of Montmartre. According to the map on your phone, your apartment is across and down the hill. In subsequent days, you’ll learn to avoid this touristy summit, but today, you go right through the thick of it.

It is on the early side of the lunch hours, always plural in France. Café tables line the streets around the square with their trim rattan chairs, waiters casually aloof yet right there with a café crème. In the center of the square are where painters, silhouette cutters, caricaturists — in that gradation of artistic ability — create and sell their wares. Sacre Coeur! Le Moulin Rouge! Notre Dame! — Paris’ greatest hits, all romantically rendered in thick, shiny paint that looks as if it might melt onto the streets in rainbow globs. Tacky, you think, inwardly offended by the ugliness of it, then you quickly try to quiet that judgmental side of your mind and just look. The painters have appropriated every style imaginable. There’s a Joan Miro rendering of bateaux mooches, drifting along the Seine. There’s the Bois de Boulogne in Barbizon hues. The whole of art history is on display here. Not your taste, but clearly it sells, so it must have some merit. After all, a PhD in art history reinforces one insight: what sells is what persists.

Tempting though the outdoor tables look, you can’t imagine sitting there in your bedraggled state, with your too large suitcase and greasy hair. Onward. On the far side of the square, you take out your phone and look at your map again. It says left, so you wind that way, past the vineyard — a vineyard in the city limits! To get to your quiet cul de sac, the rue Simon Dereure, you continue to the left, à gauche, on the rue des Saules.

“You have arrived at your destination,” the lady in your GPS tells you, certain and spectral.

But you haven’t. You’re just at a place, that most French of concepts, a small intersection that has been memorialized in some way. In the middle of this particular place is statue, the upper part of a woman — her head flowing with hair, and her extravagant chest. There are a few trees, their leaves starting to change into fall yellows. A staircase descends behind the statue.

You can’t see your apartment. There must be something wrong with the GPS. As you stand there looking at your phone, you hear music, an old disco tune, the beat pulsating.

Monday! It’s just another morning. Day after day, life slips away. Laissez-moi danser!

Two young men with spiky jet black hair, Japanese perhaps, approach the statue. They stand on either side of it, and each place a hand on the woman’s breasts. One of them lifts a selfie stick into the air and they both start laughing. Souvenir de Paris! After they leave, you take a closer look at the woman. Clearly these gents were not the first to cop a feel, as her bronze bosom is burnished to a golden sheen. The plaque reads, Yolanda Gigliotti, dite DALIDA, chanteuse comedienne, 1933–1987. You will look her up online later. But first you have to figure out where you live.

You look at your phone, then at the streets entering the place. You’re close. The arrival point throbs on your map. A woman walking a small terrier comes your way. Back before there were phones, people asked directions. Desperate times call for desperate measures.

“Pardon, madame,” you say, and she stops. Her little white westie sits at her feet and looks up at you. “Je suis perdu.”

Your first French conversation, and it’s about being lost.

“Oui,” she says. It’s a statement, and not a particularly friendly one. You show her the address on the phone. “Ah oui,” she says, and she walks you over to the staircase, pointing down. “La, à droite.”

“Merci,” you say. You feel like kissing her, your relief is so strong. Now you just have to lug that damn suitcase down the stairs, make a right, and voilà. Home.

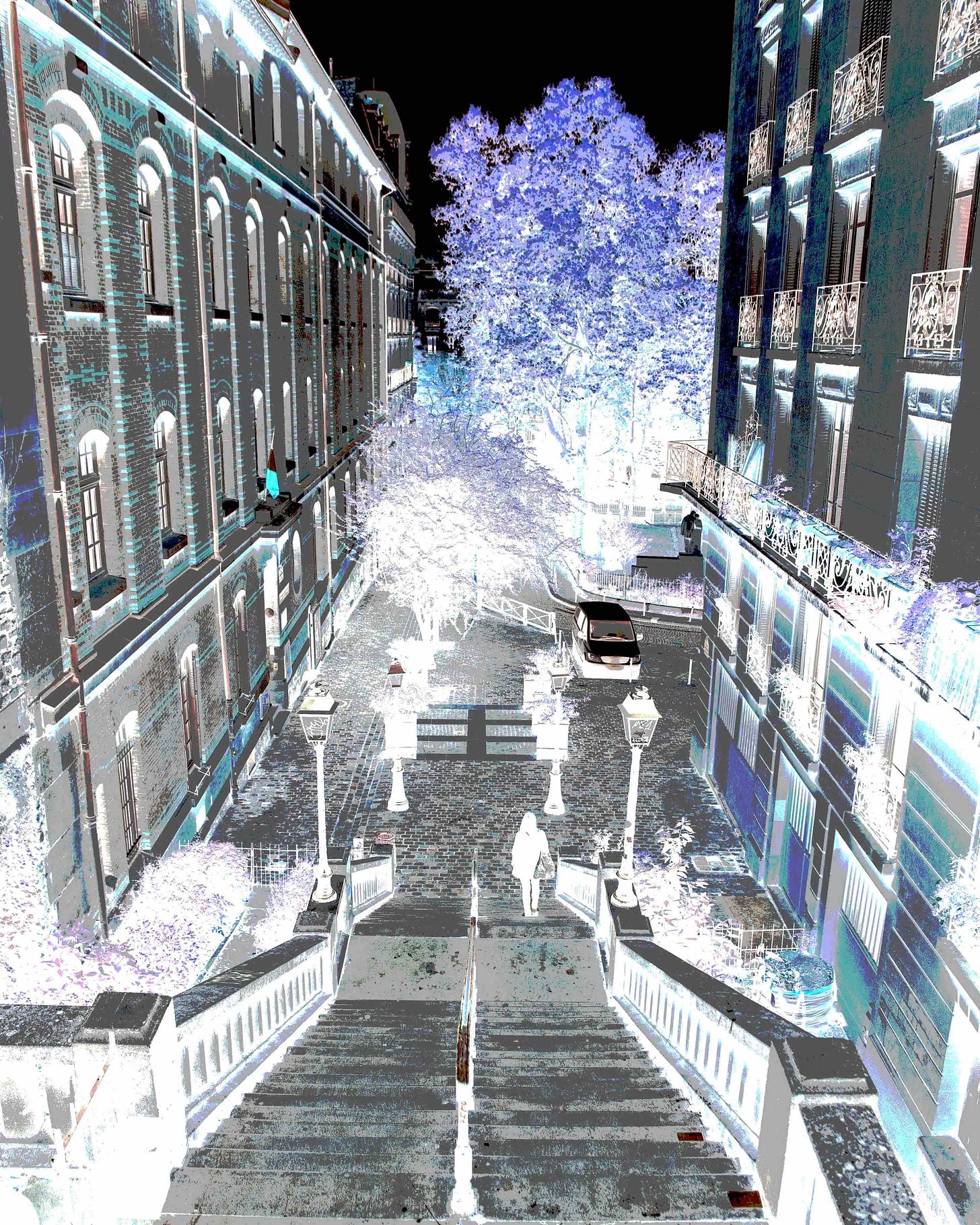

The suitcase, gargantuan, black, cheaply made, seems heavier with every step. You pause midway down and look at the view. Black street lights, slim and elegant, line the stairway, straight out of a Cartier-Bresson photo. (You find out later, Cartier-Bresson did in fact photograph these steps.)

“Pardon,” it’s a man’s voice. “May I assist?”

He is tall and dark haired, in a deep blue suit. You make out a letter — J — of tiny wrist tattoo showing beneath the white cuff of his crisp shirt. Though he is clearly French, he addresses you in English. Disappointing.

There’s a little click in your heart, a switch turned on.

“No, thank you. I have it.” It’s a reflex of yours, turning away help, not needing it whether you need it or not.

“Really?” There is an edge of amusement in the way he says this word. You see his eyes, that you thought were brown, are actually an astonishing green, like sun piercing the sea.

“Alors, bon chance.” He steps lightly down the stairs, looks up at you and walks on.

Standing on the middle of the staircase, you watch him recede in the distance. Handsome. So handsome.

Idiot!

The word, hissed in exasperation, startles you.

You look around.

The lady and her dog have moved on. The young man is long gone, and no one is snapping a portrait beside the bust at the place. You are alone.

Tuesday, I only feel like living, dancing along with every song.

The singer is in anguish — or ecstasy. Her voice and the thumpa thumpa of the beat blow you down the steps.

You hope none of your new neighbors are playing that music so loud.

At the door, the concierge looks you up and down, as much a foreigner as you are, Algerian maybe, her head covered in a bright pink scarf. You present a print out of an email between the landlady and yourself. It seems to suffice.

“Bon,” she says, and she hands you a key and gestures toward the stairwell. “Je m’appelle Basira,” she tells you, pointing to herself.

“Et moi, je m’appelle Andy,” you say. Your name sounds hard and angular compared to the soft round notes of hers.

“Annnndeee,” she says, puzzling the sounds.

“Andrea,” you say, exaggerating the -ay sound in the middle. That seems to work better for Basira.

“Pas de ascenseur?” you ask — you really want there to be an elevator.

Basira shrugs, an all-purpose gesture that today means no, maybe carries some regret but then again what could I do, it seems to ask. Living in Paris will teach you an entire vocabulary of shrugs. This is just the first lesson. The staircase winds up six stories. Light pours in from a skylight, worked over with filigree. Very belle epoque you note, and it makes the lugging of the luggage slightly more bearable.

Finally, you are at your door, number 506. You unlock it with the massive key the concierge gave you. An old skeleton key, heavy as a tibia.

The apartment is epically small, smaller than the closet you had back in New Haven, and that wasn’t a walk-in model. A single room with a table over the bathtub — you’re pretty sure that’s the actual tub, not a decorative objet. There is a double bed, a small stove and sink. An armoire with room for maybe four dresses to hang, a toilet hidden under an eave. But the windows. Two large, glorious windows. They are what sold you on the place to begin with and they live up to your hopes. You open them both and air out the room. There is a single easy chair, upholstered in gray blue. You pull it over to one of the windows and sit.

In come the noises of city life. A few small yaps from a dog. Children playing at a schoolyard. The ceaseless engine sound of cars moving through the small streets. Up above there are the famous skies of Paris, a few moody gray clouds gathering. Below, you can see the tops of trees shake in the wind. If you turn your head as far as it will go, you can even see the Eiffel Tower. You’re home.

When you wake up next, it’s just past midnight and you are all the way awake. Not groggy. Clear-headed. Vibrantly, resolutely awake. You dreamed about the Banquet of Esther, again. It’s the tapestry that earned you your Ph.D., depicting the biblical queen who refused to wear jewelry, and who hanged her uncle when he betrayed her husband. You see Esther, her feet on a cushion, a little dog drinking from a fountain. She sits beside her Persian king Ahasuerus, head tilting toward him, deep in conversation. That’s what you want, when you let yourself want that.

Still in the chair, you lean over the window sill and regard the nighttime city. The city’s hues have disappeared, as if they’ve taken to bed and left the world in a monochrome state, and now you’re in a black and white photo.

Monday, it’s just another morning.

Not again. That old relic of a disco song, full of panting longing. Who the hell is playing it this late?

Laissez-moi danser chanter en liberté tout l’été.

You listen more intently, trying to figure out where it’s coming from. Whoever is singing has an accent. Not French, not American or English or Spanish.

Then it hits you. It’s coming from your room.

Moi je vis d’amour et de danse.

“I live on love and dance?” God, the lyrics. So corny.

The voice starts to sing the chorus.

Day after day life slips away!

You check your phone. Maybe you left your music on? No. You didn’t do that. You’re always careful about closing your apps to preserve battery life. And you don’t listen to a lot of disco.

What’s the matter, darling?

Now it’s speaking to you, this woman’s voice, heavily accented. It sounds like perfume and cigarettes and silk night clothes.

Didn’t you know you had a roommate?

“What?” You say this to confirm what you already know. This is not your own voice speaking.

I saw you today.

Your heart feels like it would run away if it weren’t for this damn skin holding it in.

“What the fuck?” You’re not a dropper of f-bombs but it seems warranted.

I saw you shoo that man away. You are a fool. You don’t deserve my apartment.

You grab your purse and leave, locking the door behind you. Then you run down the stairs and into the Parisian night.

Gasping for breath, you stop and look around. You’re in a city you don’t know, and you don’t know anyone. You have a job of sorts, but it hasn’t started yet. You are completely alone and anything could happen to you.

One side of this thought is fear, something entirely familiar. The other side of it, though — something new. Anything could happen.

You walk downhill and your breathing starts to settle. The night is quiet but for a breeze that sends leaves down to rustle behind you. You look at your phone. 12:46 in the morning. You call Joel back in New Haven. You just need to hear his voice.

“Hey thanks for the call. Leave a message.” Where is he?

“Call me, ok? I just…” What can you say about what happened actually? You heard some old music and freaked out? “I just miss you.” It’s almost true.

There is a café down the street and the light is still on so you walk toward it. Inside, there is a waitress leaning on the bar looking at her phone and a man behind the bar looking at his.

“Allô?” you say. “Ouvert?”

The man looks up and shrugs, which you take to mean yes.

“Thé camomille, s’il vous plaît” you say, and they look puzzled.

“Comment?” the waitress says. Close cropped dark hair, a nose ring, giant brown eyes. She’s waiting for you to say what you want and you thought you did.

“Um, chamomile tea?”

“Ah, tisane,” the waitress says, in a eureka moment. Tea, of course, is the word reserved for black or green tea, not herbal infusions, which go by tisane.

If you can’t even order a cup of herbal tea, there is no way you could describe what just happened. Un petit cauchemar, perhaps — a little nightmare? Whatever it was, you don’t have the vocabulary for it. The café has a long wooden bar with the array of alcohol-specific glassware, different glasses for different beers, for different brands of pastis, and of course, for wine. The barman hums along to the music, Al Green lamenting how he’s so tired of being alone. What is it with Paris and 70s music, you wonder. But it’s such a good song and the tea — tisane — of steeped flowers soothes you and maybe it was just a bad dream invoked by jetlag and stress, being a stranger in a strange land and all. You pay up and go back into the night.

Stepping onto the sidewalk, you stop and listen. Quiet. The street is empty. You’re walking home in the early hours in Paris. You pause to breathe in the cool air a little moist, maybe rain on the way, a smell of fall and possibilities.

When you return to your apartment, the chair is at the other window, the opposite side of your tiny room. You know you didn’t put it there.

Day after day, life slips away.

Your stomach is upset. That is the perfect description. It’s a disconsolate child, unwilling to stop seizing up in anxious spasms, clenching tight. It won’t be comforted no matter how well prepared you are for the next morning, when everything begins. And you are prepared. You have studied your options for getting to the Gobelins Manufactory — Google offers three routes, all varying in length but within a few minutes of each other. You plan to take the metro. But what if there’s a strike? That happened once before when you were here and you strained to understand the muffled announcement that had suddenly cleared the platform. You have checked the news, you tell your stomach. No strikes planned.

Then your internal alarm clock goes into overdrive. Is it time to get up yet? No? Three more hours? Sure, I’ll go back to sleep. So it goes, every hour on the hour.

In the morning you put on the blouse you have chosen for today, grey silk with a pattern of grey roses. It’s perfect, you think, for your first day. It nods toward tapestry, but with a modern edge.

You look like wallpaper.

Everything in you tightens.

Do not wear that.

Suddenly there is sweat on your upper lip and beneath your armpits — you can practically smell your own fear.

Her voice is accented but emphatic.

You peer into the mirror and swear you can almost see her, dancing like smoke.

Wear the purple one.

You do, in fact, have a purple blouse — you bought it yesterday at a vintage shop in the Marais. Purple isn’t your color but something about its deep plum hue caught your eye. It made you happy with its sheen and extravagant neck bow. Very 80s.

With the grey pants.

You pull the clothes and it’s true, they look great together. You put on a pair of black shoes, flats. They’ll be comfortable for the commute, and since you’re tall, you won’t intimidate anyone with your height.

Do not wear flats. Those black kitten heels.

You obey this voice, though you don’t know why. Together, you and your invisible roommate, take a last look in the mirror.

There. You look memorable.

You leave the apartment, dressed as instructed. Scared, technically, that is the official word. But something else, too. Is it the shirt? The heels? For once, you do feel memorable.

The week days make your life in Paris feel normal. You commute on the metro, you have your coffee shop, where the waitress, Apolline, is almost friendly now. Well, not surly at least. At work, you experience moments, fleeting moments, of a new feeling. It might be joy. It washes over you as you walk from your workstation to the restroom, a sense of being exactly where you should be, doing the thing you’re on earth to do. You are no stranger to tapestries. Your thesis required you to work with the Esther cartoon and finished work in an intimate way. But being among so many, all day every day, getting a feel for the scale of the enterprise, the planning and resourcing that went into providing these to the great homes of Europe — that aspect has opened up a new research avenue, and it thrills you. You start to see how your life might be shaped and the shape is more beautiful than you can believe. Your colleagues don’t speak English to you anymore. Instead, they fussily correct your French. At first this offended you, but you are starting to realize, it’s a compliment. Your French is good enough to merit improvement. There’s hope.

Coming home late on a November day, you hear the accordionist on the street starting up on yet another round of Sous le Ciel de Paris for passing tourists. That iconic song has become a talisman for all that is not your Paris, and you’re becoming quite possessive of this city. But today, you don’t mind him, and that granting of an inch feels like progress. You had a therapist in Connecticut who worked with you on breathing technique so that you could manage the anxiety, the urge to control every little thing, that kept you from the rest you dearly wanted. Now you seem to sleep just fine, and if you’re awake occasionally, it’s not so bad. In fact, it’s lovely to look out your window at the city in its infinite coil of glitter, always changing.

You turn onto the rue Lamarck. Anouk Aimee, in the movie “A Man and a Woman,” stars as the chic young widow with the beautiful daughter. She says those words, “Rue Lamarck,” to Jean-Louis Trintignant, the single father race car driver, who gives her a ride home from the school their children attend in Normandy. Saying the plot to yourself now, it sounds like a game you would have played as a child, a fantasy of romance, which of course it is.

Coming home through the Place, you see two men — they look Scandinavian — taking selfies at the Dalida statue.

We are going out tonight. Get dressed.

You stop and look at the men, but it’s a woman’s voice, and they are oblivious to you, laughing at their pictures.

You had planned to read up on the wool market of 1681. A lot of money was made and lost that year.

It’s Saturday night. You are not reading about wool.

It’s true that you have not ventured out on a Saturday night — or any other night for that matter. You’ve shopped in the evening, if that counts, picking and choosing among the market stalls or stopping by the butcher for what you need. You can ask for meat by the correct weight in kilograms now, and you get the money right each time. No more guesswork or over paying. But you haven’t ventured into the restaurants where it seems each table houses the best conversation, there between friends, there between lovers, all bathed in golden light. You’ve been on the other side of that glass.

You will never have any fun unless you go make it.

“Who says I want to have fun?” you say opening the door to your apartment.

Just look at you. You need it.

You stand before the mirror, appraising. Your eyes look tired. Prepared for disappointment, even as you live in the city of your dreams, doing the work of your heart. How can that be? Then the familiar tallying of faults and its keening lament starts — too much around the hips, too small up top, nose a bit wide, hair unruly. If only you’d gotten your dad’s legs and your mom’s boobs, but it went the other way.

As if men knew what to do with them anyway.

Somehow you know she means boobs.

You’ve seen them at my statue, squeezing until they shine. Just like when I was alive, but it hurt more then.

“You’re her? Dalida?”

Of course. Who did you think?

You hadn’t really thought about it, actually.

“But aren’t you,” you’re not quite sure how to say this, not wanting to offend. “Haven’t you passed away?”

I killed myself in 1987, not that time means anything.

“I’m sorry.”

How do you express condolences to a ghost?

“My life is unbearable, forgive me.” That’s what I wrote. It was true then — that’s how it felt anyway. But now, I don’t know. Life looks so delicious.

You think about the café crème you had this morning and you have to agree.

Just once more, I want to drink champagne. Sing again. Make people dance. Watch them be happy. Because of me.

You open the door to your closet and consider your options.

Wear the black dress.

You put it on as commanded.

“How do you know about me?”

I picked you.

“What do you mean, you picked me?”

I lived here when I was starting out. It was a happy place. So when the landlord makes her selections, I help. It’s one of the prerogatives we specters have. I felt sorry for you as soon as I saw you.

You hear long puff, like someone dragging on a cigarette, and an exhale. Then you smell smoke. Not an altogether bad smell, but you feel yourself shaking.

After all, you’ve never been a smoker.

Wasting away. Not that work is a bad thing. It’s just not the only thing. Never going out. Never laughing. No lover to make you shiver. Quel waste.

“I worked so hard for this,” you say.

It’s true, too. You beat out who knows how many others for the fellowship dollars. You’re not timid.

Then don’t waste it. Put on some lipstick. Brush your hair.

You do those things and the woman you see is the one you’ve been waiting to show up. The dress clings in the right ways, your hips the start of a glorious curve. You look smart. You’d have something interesting to say.

“Where am I going to go, dressed like this?”

You’ve never been a party girl. That wasn’t your kind of fun. Your kind was talking all night with your best friend, or a lover. There have been shivers and you have a gift for recognizing someone who will be important to you in the exact moment you see them. A switch turns on. Your heart takes a little picture — Click! — and then they turn up again, somehow, every time.

But to go out alone on a Saturday night in a slinky dress — not your thing.

Don’t worry about it. It’s Paris.

The night has a frosty edge, the cold knife of winter starting to cut through you as you walk. Up ahead is a brasserie, light bouncing off the brass rail behind the banquettes. It has a bar where you could stand but it is full of men taking up the space, no doubt talking about soccer scores and other things that bore you. Tonight you don’t want to feign interest in a second language. You walk on.

Looking down a side street, a hanging lamp calls you. This is not a part of the neighborhood you’ve walked through before. There is a hardware store with a window full of aging locks displayed in regimental lines. Next to it, an épicerie showcases its wares with irresistible panache. Tins of tuna feature portraits of steel blue fish. Tiny jam pots coo in the exquisite language of berries — framboise! fraise! Bottles of oil dressed in festive bronze cellophane. The little spot next door has a simple slate sign in the window — bar à vin, ouverte. Inside the light is dim but for a shimmer of votive candles landscaping tables, bar, shelves. You see a few plats so they must have food. You push open the door.

“Bon soirée,” a woman walks over, puts her arm in yours. She asks if you’re expecting anyone else.

“Not that I know of,” you tell her, amazed to bring it off in French.

“Très bien,” she says. “A woman who can dine alone is a woman who can live.” She places you at a table along the back wall, a proper table, not relegated to the kitchen doorway. She pulls the out so that you can slide onto the cushioned bench.

You order a coupe de champagne — you love this phrase, literally like a cut of champagne, a blast of it, something that blows through your life in delightful bubbles. You take in the room while the waitress fetches it. The long zinc bar and bent wood barstools tip toward the past. But the spare lines and simple candles, the monochrome palette, all grays and whites, give the room a soothing modernity. All punctuated by a bouquet of red roses dramatically lit on the bar.

It’s a good night to gaze out the window and as you do, you see the first snowflakes. Unhurried, silent, floating, turning, dancing.

Then the waitress returns with your glass of sparkle. She suggests oysters from Cancale, way out at the edge of Brittany, flat belons that taste like a wave at high tide. You say yes and sip the champagne. A little smear of lipstick kisses the glass.

“Pardon,” says a man, bumping your table as he walks by. You spot the J tattooed on his wrist. The man from the staircase.

Don’t be an idiot. Say something.

It’s the cigarette and silk voice. Dalida, your roommate, here with you.

“Oh hello,” you say and you can’t believe you say it.

“Hello?” he says, looking at you more closely. “Ah! Bon soir to you.” Apparently he recognizes you. “How is your suitcase?”

He smiles.

“It is well. Sleeping now, I think.”

“Bien sûr.” Of course. He puts his hands in the prayer position and rests his head on them, feigning sleep.

His nose is red from the cold. He wears a blue wool coat that graces his knees, lightly dusted with snow.

Invite him to sit with you.

“Join me?” you offer, and you wonder, in that moment, who you are.

“I would like that.” He sits. “Je m’appelle Jean-Marc.”

Finally, he speaks to you in French.

“Andrea. But my friends call me Andy.”

“Andy, then. Enchanté. Tell me, then, Andy, why you are here.”

So you do, about tapestry and the Gobelins and Paris.

He’s a lawyer for an environmental organization, bringing suits against oil companies. He shows you the tattoo — it says jusqu’au bout, until the end.

“It’s to go the whole way, with my whole heart, wherever it takes me,” he explains. “It’s the only way, don’t you think?”

You agree. You talk through a second glass of champagne that gives way to red wine to complement your beef daube and his chicken.

A man with a guitar comes in and sets up a microphone and amplifier.

“This guy,” Jean-Marc says. “He is why I come here.”

The man sings “Samba Saravah,” and there’s Anouk Aimee again, now she’s riding a horse through the Camargue, her stunt-man husband and their friends riding along. Before he is killed.

When someone calls out for Pink Floyd, his contemplative opening to “Wish You Were Here” brings cheers.

You feel Dalida moving like smoke.

Go sing.

“I can’t.”

Jean-Marc looks at you. “What can’t you do?”

“I can’t sing,” you say.

You won’t be singing.

“I’ll make a fool of myself,” you say. That is not something you want to do in front of this handsome man who turns out to be an interesting person.

“I doubt that very much,” he says. “What would you like to sing?”

Laissez-moi danser! Let me dance!

Did she say that or did you?

It doesn’t matter, because Jean-Marc is talking to the guitarist, who looks at you then smiles, surprised, and gestures you over to the mic.

Now you’re standing up, walking across the floor and people are applauding as the man shares that you’ll be singing the number one disco hit of 1979, a classic from Montmartre’s favorite chanteuse, Dalida.

“Mesdames et messieurs, veuillez accueillir Andrea qui chantera Laissez Moi Danser!”

Please welcome Andrea.

Though you’re terrified, the guitarist starts beating out your thumpa thumpa rhythm, and the diners join in, like they are beating your heart for you. He begins the guitar riff and sings the intro — “Monday, it’s just another morning! Tuesday, I only feel like living” — and then it’s you, singing, “Aller jusqu-au bout de reve!”

Go to the end of the dream.

You move like smoke, like silk nighties, like perfume across warm skin. She’s singing in you, dancing in you, smiling at the crowd that’s smiling at you. When it’s done and they’re clapping and whistling and cheering and pounding the tables, inside, the sighs you feel are hers.

Jean-Marc comes over and takes your hand. You bow and return to your seat.

“That was fun,” you say, though it might have been her speaking. You’re not sure anymore.

“May I walk you home,” Jean-Marc asks. This is an easy one. You don’t need Dalida to tell you what to do.

“Oui.” Yes. That’s kind of you. Très gentil. Thank you.

You walk together in the falling snow, the city hushed, your breath and his mingling as you talk. At the door he asks for your number.

“I’d like to see you again, Andy, disco queen with a Ph.D.” His smile is deep and full of warmth.

You share it with him and there is a moment, then he kisses your cheeks, Gallic style, one two, but adds a third kiss, closer to your mouth. A possibility.

Très bien.

It’s her voice, lifting into the sky, fainter and fainter as snow falls on your warm cheeks.

Jean Shields Fleming is the founder & editor-in-chief of Certain Age, a Substack top 100 publication in Culture. Her novel Air Burial was published by Carrol & Graf, and you can read an excerpt from her latest novel, All The Reasons Why.

If you enjoyed reading this post, please give it a like ❤️, restack it, or comment. Thank you!

Photo credits:

Montmartre staircase by Max Avans

Cafe chairs by Marta Siedlecka

Dalida images by Jean Shields Fleming

So many things to say about this lovely piece!!! This line though- “An old skeleton key, heavy as a tibia.” Wow! Well done! ❤️

Oh, this was so sensuous and delicious!! I loved it!!